Comparing Julia, C++, Fortran, and Python Run Times with Coin Flip Code

I’m a computational materials scientist, and naturally, I enjoy programming. Recently, I’ve been thinking about picking up a programming language other than Python to help prepare me for a post-doctoral position at a national lab. I was having a hard time choosing between C++ and Fortran. On the one hand C++ would be pretty useful because it’s the language that LAMMPS is written in and so I could extend LAMMPS to fit my needs. On the other hand, Fortran is used in NASA Glenn’s MAC/GMC code (along with tons of other legacy code) and I would love to work with the micromechanics group at NASA Glenn someday. And then I found Julia which is a programming language designed for parallelism and cloud computing and combines the ease of Python with the speed of C++/Fortran, but it is still in beta (v0.6.3 is the current version). All three would be very useful to have at my disposal. Since I have a lot of time on my hands right now, I’m going to try to learn all three.

The best way to learn a new programming language is not through a course or a book, but by trying to do something with that language. I set out to create simple coin flipping scripts in Julia, C++, Fortran, and Python (for comparison) and then time them all. I also created parallel versions for each language. In this blog post, I will go through each language’s code and then report on the timing of each script.

This is a pretty long post so I’ve provided a few links to jump to the Fortran, C++, Julia, and coding resources sections below. Fortran, C++, Julia, and coding resources

Below is the Python code.

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-

"""

Created on Mon Jul 02 00:16:48 2018

@author: wapisani

A simple coin flip function.

"""

# Define coin flip function

def coin_flip(times):

count = 0

i = 0

while i < times:

count += int(bool(random.getrandbits(1)))

i += 1

return count

if __name__ == '__main__':

#The above check ensures that I can import the above functions from a different script.

#Essentially kind of a future proofing technique.

import time

import multiprocessing as multi

from multiprocessing import Pool

import random

#Start timer

start_time = time.clock()

# Define variable that determines if this script runs in parallel or not

# 0 is no, 1 is yes

parallel_flag = 0

# Initialize number of flips

num_of_flips = 10E8

# Print program statement

print("This script will flip a coin {:2.0E} times and report the number of heads\n.".format(num_of_flips))

# Branch

if parallel_flag == 1:

# The typical desktop i7 has four cores with hyperthreading

# enabled for a total of 8 cores. multi.cpu_count() will tell you how

# many total cores are in your computer.

#Parallel processing code

# Define number of cores to run with

num_of_cores = 4

# Print the number of cores running

print("Running coin flip script with {} cores in parallel".format(num_of_cores))

#Create process pool with specified number of processes

pool = Pool(processes=num_of_cores)

# Create a work array that even divides up the work between

# the number of cores

work_array = [num_of_flips/num_of_cores for value in range(num_of_cores)]

#Have each process take a quarter of the work

results = pool.map(coin_flip,work_array)

#Each process returns a quarter of the total number of flips

#so sum them together

count = sum(results)

#Terminate processes

pool.terminate()

#Wait for processes to exit

pool.join()

#Note: Processes are still present in RAM. Need to figure

#out how to remove them from RAM.

print("The number of heads is {}.".format(count))

print("The percentage of heads is {:.5%}".format(count/num_of_flips))

print("Time taken: {} seconds".format((time.clock() - start_time)))

else:

print("Running coin flip script with one core")

# Run coin flip function 10^8 flips

count = coin_flip(num_of_flips)

print("The number of heads is {}.".format(count))

print("The percentage of heads is {:.5%}".format(count/num_of_flips))

print("Time taken: {} seconds".format((time.clock() - start_time)))

All code was run on an Intel Core i7-7700 clocked at 3.60 GHz (turbo boost up to 4.20 GHz) with 4 cores and 8 logical cores.

The random library in Python seems much more developed than the equivalent options in C++ and Fortran, though that could just be speaking to my inexperience with C++ and Fortran. random.getrandbits(1) retrieves a random bit and that bit is then converted into a bool (True or False) and then into an int (1 or 0). 1’s are considered to be heads. Though this code can handle larger numbers than 10E8, all run times are limited to 10E8 due to a RAM limitation in the Fortran code.

| Flips | Number of Cores | Run Time (sec) | Speed Up |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10E8 | 1 | 407.2 | 1 |

| 2 | 205.7 | 1.98 | |

| 3 | 148.7 | 2.74 | |

| 4 | 130.7 | 3.11 | |

| 5 | 116.5 | 3.50 | |

| 6 | 112.9 | 3.61 |

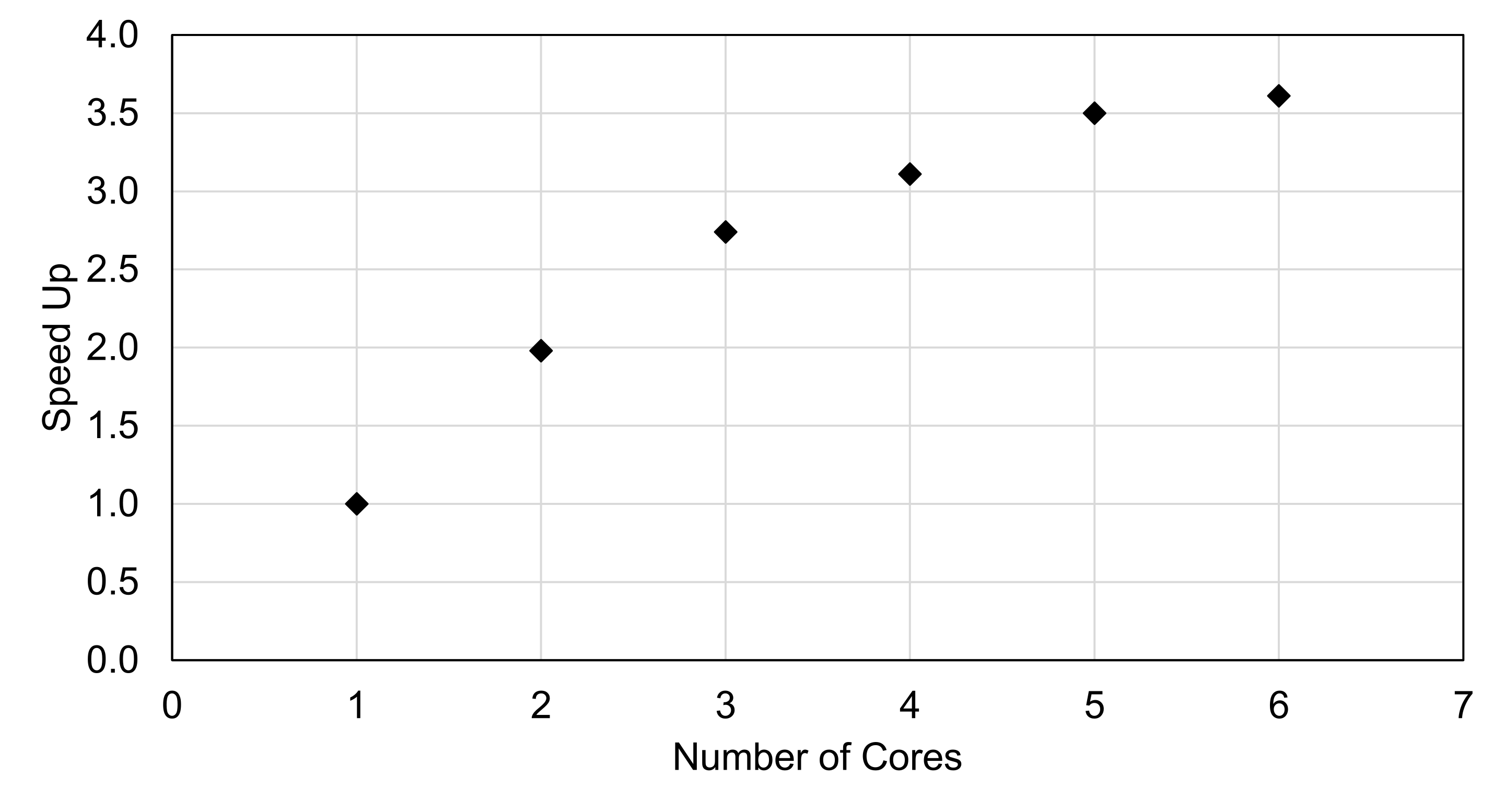

As seen in Table 1, using two cores cuts the run time in half while four cores gives a speedup of three times. It’s interesting that five cores gives another 14 seconds of speedup because hyperthreaded cores are not usually known to benefit parallel programming. The following is dependent on exactly what you’re doing (i.e. int operations vs floating point operations) and your processor architecture, but in general it’s true. A hyperthreaded core has two logical cores that can be scheduled simultaneously, but both cores can’t run instructions at the exact same time because only one core physically exists. So the two logical cores switch back and forth quickly. Generally, high performance computing (HPC) clusters have hyperthreading functionality turned off because the performance of most HPC software is adversely affected with hyperthreading on. Figure 1 shows the speed up as a function of number of cores. There is nearly a linear relationship up to 3 cores, but then the curve levels off.

! coin_flip_omp.f90

!

! FUNCTIONS:

! coin_flip - Entry point of console application.

!

!****************************************************************************

!

! PROGRAM: coin_flip

!

! PURPOSE: A simple parallel coin flipping program

! CREATOR: Will Pisani

! DATE: July 2, 2018

!

!****************************************************************************

program coin_flip_omp

! Import libraries

use omp_lib

implicit none

! Variables

integer, parameter :: MyLongIntType = selected_int_kind (10)

integer (kind=MyLongIntType) :: num_of_flips = 10E8

integer (kind=MyLongIntType) :: count = 0, j, i

integer :: proc_num, thread_num

real, allocatable :: rand_num_array(:)

real :: seconds, seconds_rand_array

! Begin timing program

seconds = omp_get_wtime()

! Allocate rand_num_array

allocate(rand_num_array(num_of_flips))

! Program statement

print *, 'This program will flip a coin', num_of_flips, 'times and report on the number of heads'

! Generate an array num_of_flips long of random numbers

call RANDOM_NUMBER(rand_num_array)

! Get time used to create random array

seconds_rand_array = omp_get_wtime() - seconds

print *, 'Time to generate random array on one core: ', seconds_rand_array, 'seconds'

! How many processors are available?

proc_num = omp_get_num_procs()

thread_num = 2

! Set number of threads to use

call omp_set_num_threads(thread_num)

print *, 'Number of cores is ', proc_num

print *, 'Number of threads requested is ', thread_num

! Start while loop

!$OMP PARALLEL DO REDUCTION(+:count)

DO j = 1, num_of_flips

! if the jth value is less than 0.5, then call it heads

IF (rand_num_array(j) < 0.5) THEN

count = count + 1

END IF

END DO

!$OMP END PARALLEL DO

! End timing

seconds = omp_get_wtime() - seconds

! Print the number of heads

print *, 'The number of heads is ', count

print *, 'The percentage of heads is ', dble(count)/dble(num_of_flips)*100

print *, 'Time taken to tally up heads: ', seconds - seconds_rand_array, 'seconds'

print *, 'Total time taken to run:', seconds, 'seconds'

end program coin_flip_omp

My first draft of this code was written very similarly to the Python code, but it was taking uncharacteristically long for a Fortran program to run. On a single core the code took ~200 seconds and two cores took ~800 seconds to run. The reason was “that calling RANDOM_NUMBER inside a parallel region will introduce lock contention as there is a single seed per program.” The current version of the code is significantly faster as you’ll see in the next table. Unfortunately, generating an array 1x10E8 filled with real numbers takes up a significant amount of RAM (3.8 GB, as seen in task manager on Windows 10) and an array 10E9 would take more RAM than I have. The Fortran code builds an array 10E8 long and populates it with random (real) numbers between 0 and 1. Then it goes through the array and tallies up the heads. One core builds the random array which takes ~3.9 seconds. The timings in Table 2 are the times the code took to tally up the number of heads and not the total time taken by the entire program.

| Flips | Number of Cores | Run Time (sec) | Speed Up |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10E8 | 1 | 3.979 | 1 |

| 2 | 2.071 | 1.92 | |

| 3 | 1.339 | 2.97 | |

| 4 | 1.027 | 3.87 | |

| 5 | 0.890 | 4.47 | |

| 6 | 0.723 | 5.50 |

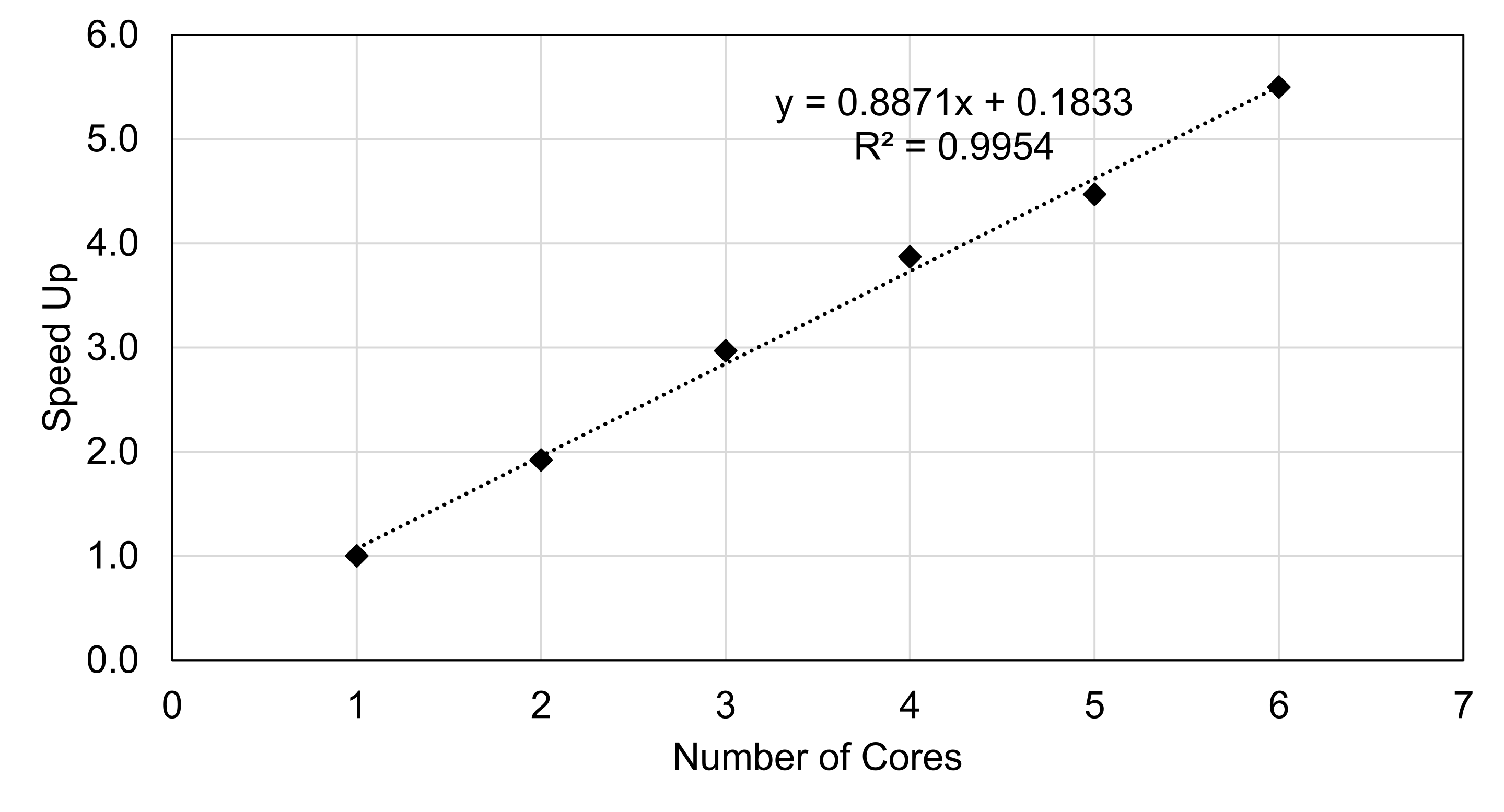

It’s interesting to see the difference between the Python and Fortran timings. While there is not a linear relationship between speed up and number of cores with the Python code, there definitely is a linear relationship with the Fortran code as shown by the trendline in Figure 2.

// coin_flip.cpp

// Purpose: A coin flipping program with OpenMP

// Creator: Will Pisani

// Date: July 3, 2018

#include "stdafx.h"

#include <cstdlib>

#include <ctime>

#include <cstdio>

#include <iostream>

#include <iomanip>

#include <random>

#include <omp.h>

// Timer code taken from https://stackoverflow.com/questions/17432502/how-can-i-measure-cpu-time-and-wall-clock-time-on-both-linux-windows

// Mysticial's solution

// Windows

#ifdef _WIN32

#include <Windows.h>

double get_wall_time() {

LARGE_INTEGER time, freq;

if (!QueryPerformanceFrequency(&freq)) {

// Handle error

return 0;

}

if (!QueryPerformanceCounter(&time)) {

// Handle error

return 0;

}

return (double)time.QuadPart / freq.QuadPart;

}

double get_cpu_time() {

FILETIME a, b, c, d;

if (GetProcessTimes(GetCurrentProcess(), &a, &b, &c, &d) != 0) {

// Returns total user time.

// Can be tweaked to include kernel times as well.

return

(double)(d.dwLowDateTime |

((unsigned long long)d.dwHighDateTime << 32)) * 0.0000001;

}

else {

// Handle error

return 0;

}

}

// Posix/Linux

#else

#include <time.h>

#include <sys/time.h>

double get_wall_time() {

struct timeval time;

if (gettimeofday(&time, NULL)) {

// Handle error

return 0;

}

return (double)time.tv_sec + (double)time.tv_usec * .000001;

}

double get_cpu_time() {

return (double)clock() / CLOCKS_PER_SEC;

}

#endif

using namespace std;

int main()

{

// Declare variables

long num_of_flips = 10E8;

const long row = 10E8;

double count = 0;

// Start timing

double wall0 = get_wall_time();

double cpu0 = get_cpu_time();

// Program statement

cout << "This program will flip a coin " << setprecision(15) << num_of_flips << " times and report on the number of heads.\n";

#pragma omp parallel num_threads(4)

{

// Print number of threads in use

if (omp_get_thread_num() == 0)

{

cout << "Number of threads: " << omp_get_num_threads() << endl;

}

// Set random number generator

// Each thread needs a seed which is why the following code is in the pragma section

//srand( (unsigned int)time(NULL));

std::random_device rd; // Will be used to obtain a seed for the random number engine

std::mt19937 gen(rd()); //Standard mersenne_twister_engine seeded with rd()

std::uniform_int_distribution<> dis(0, 1);

// Start for loop

#pragma omp for reduction(+:count)

for (long i = 1; i <= num_of_flips; i++)

{

// Flip a coin and add it to the count.

// Each flip can only result in 0 and 1

// so each 1 will be treated as heads.

count = count + dis(gen);

}

}

// Stop timing

double wall1 = get_wall_time();

double cpu1 = get_cpu_time();

// Print the number of heads

cout << "The number of heads is " << setprecision(15) << count << ".\n";

cout << "The percentage of heads is " << count / num_of_flips * 100 << endl;

cout << "Wall Time = " << wall1 - wall0 << " seconds" << endl;

cout << "CPU Time = " << cpu1 - cpu0 << " seconds" << endl;

return 0;

}

I used Mysticial’s solution for getting the wall time and cpu time of OpenMP C++ code because it was the best solution I could find. This code works similarly to the Python code in that it generates a random integer on each loop. This code was easier to write than the Fortran code since I’ve had some experience coding with C/C++ and OpenMP (and MPI) during two awesome courses I took at Michigan Tech called UN5390/5391 Scientific Computing 1/2 (thanks Gowtham!). There is still room for improvement in the OpenMP sections, but it works well as is.

| Flips | Number of Cores | Run Time (sec) | Speed Up |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10E8 | 1 | 11.82 | 1 |

| 2 | 6.39 | 1.85 | |

| 3 | 4.56 | 2.59 | |

| 4 | 4.01 | 2.95 | |

| 5 | 3.88 | 3.05 | |

| 6 | 3.35 | 3.53 |

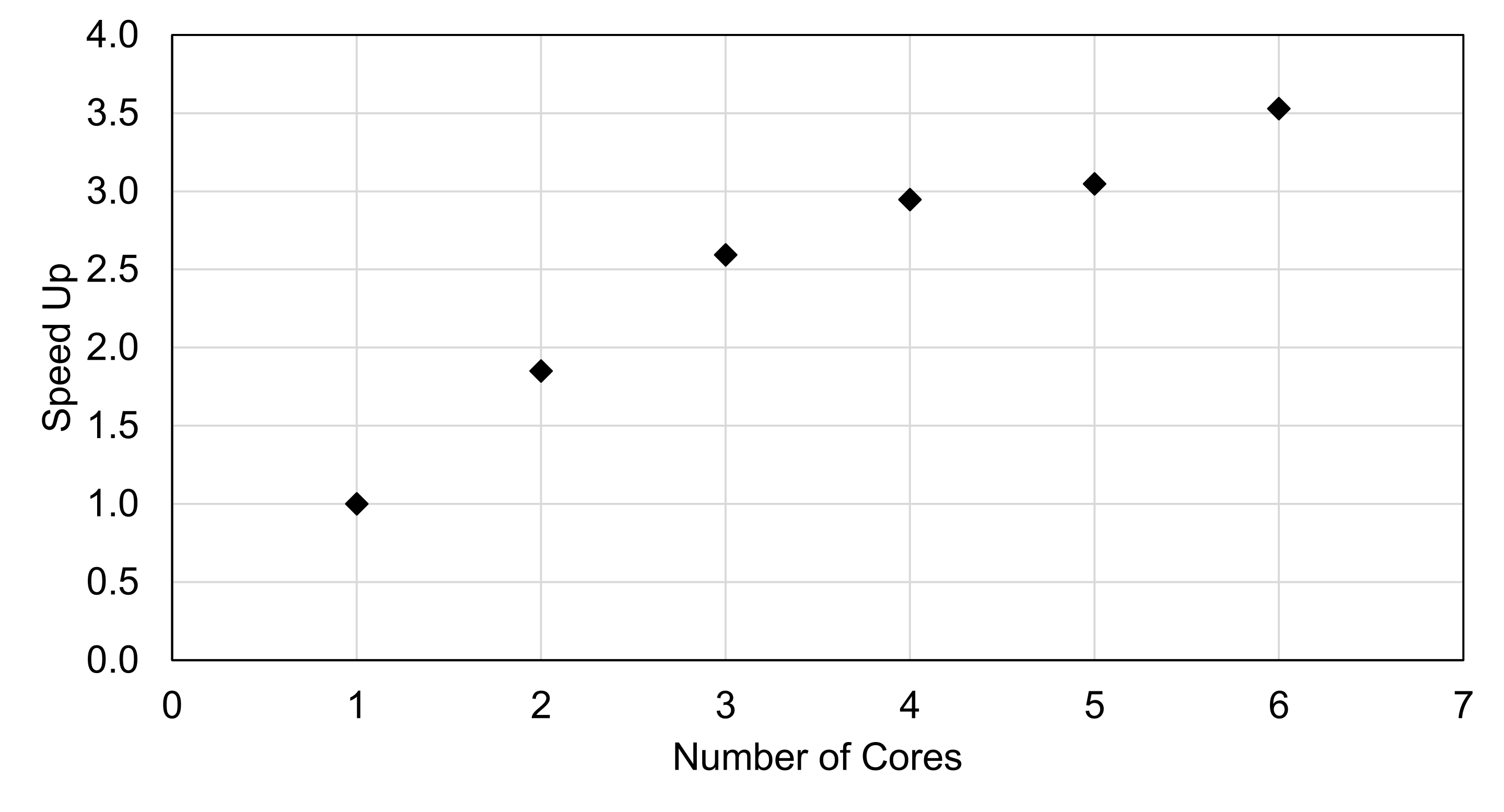

The C++ timings are shown in Table 3 and the speed up trend is shown in Figure 3. The speed up trend is similar to the Python code, which is interesting. I would have figured that the C++ and Fortran scaling would be similar since they share the same parallelization backend.

#=

Parallel coin flipping code

Code mostly from Seven More Languages in Seven Weeks

=#

# Define a variable for number of flips

num_flips = 10^8

println("\n\nA coin will be flipped $num_flips times.")

# Define single proc coin flip function

function flip_coins_single(times :: Int64)

count = 0

for i = 1:times

# Generate a random Bool (true or false) and convert

# that bool to an integer. Increment the count by

# that integer (0 for false, 1 for true).

count += Int(rand(Bool))

end

println("The number of heads is $count.")

end

# Run single proc coin flip function and time it

println("\nRunning single process coin flip function.")

@time flip_coins_single(num_flips)

# Define parallel coin flip function

function pflip_coins(times)

nheads = @parallel (+) for i = 1:times

Int(rand(Bool))

end

println("The number of heads is $nheads.")

end

# Add four worker processes

num_of_proc = 1

addprocs(num_of_proc)

println("The number of cores is $num_of_proc.")

# Run parallel coin flip function

println("Running parallel coin flip function.")

@time pflip_coins(num_flips)

# Remove added worker processes

rmprocs(workers())

Julia is an interesting language; it’s easy to learn and very fast. I hope it achieves 1.0 status soon. With this program, I defined two functions: a single core version and a parallel core version. The Python code is actually based on this Julia code. I discovered Julia (and this coin flip algorithm) in an interesting book called Seven More Languages in Seven Weeks: Languages That Are Shaping the Future. Julia is surprisingly the fastest of the four languages I tested. The timings in Table 4 are for the parallel function.

| Flips | Number of Cores | Run Time (sec) | Speed Up |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10E8 | 1 | 0.404 | 1 |

| 2 | 0.336 | 1.20 | |

| 3 | 0.325 | 1.24 | |

| 4 | 0.339 | 1.19 | |

| 5 | 0.364 | 1.11 | |

| 6 | 0.380 | 1.06 | |

| 10E9 | 1 | 2.09 | 1 |

| 2 | 1.27 | 1.65 | |

| 3 | 1.01 | 2.07 | |

| 4 | 0.9 | 2.32 | |

| 5 | 0.81 | 2.58 | |

| 6 | 0.79 | 2.65 | |

| 10E10 | 1 | 18.04 | 1 |

| 2 | 9.6 | 1.88 | |

| 3 | 6.95 | 2.60 | |

| 4 | 5.78 | 3.12 | |

| 5 | 5.15 | 3.50 | |

| 6 | 4.95 | 3.64 | |

| 10E11 | 1 | 180.08 | 1 |

| 2 | 92.21 | 1.95 | |

| 3 | 69.12 | 2.61 | |

| 4 | 55.76 | 3.23 | |

| 5 | 48.8 | 3.69 | |

| 6 | 44.38 | 4.06 | |

| 10E12 | 1 | 1771.9 | 1 |

| 2 | 942.4 | 1.88 | |

| 3 | 670.5 | 2.64 | |

| 4 | 543 | 3.26 | |

| 5 | 481.9 | 3.68 | |

| 6 | 439.5 | 4.03 |

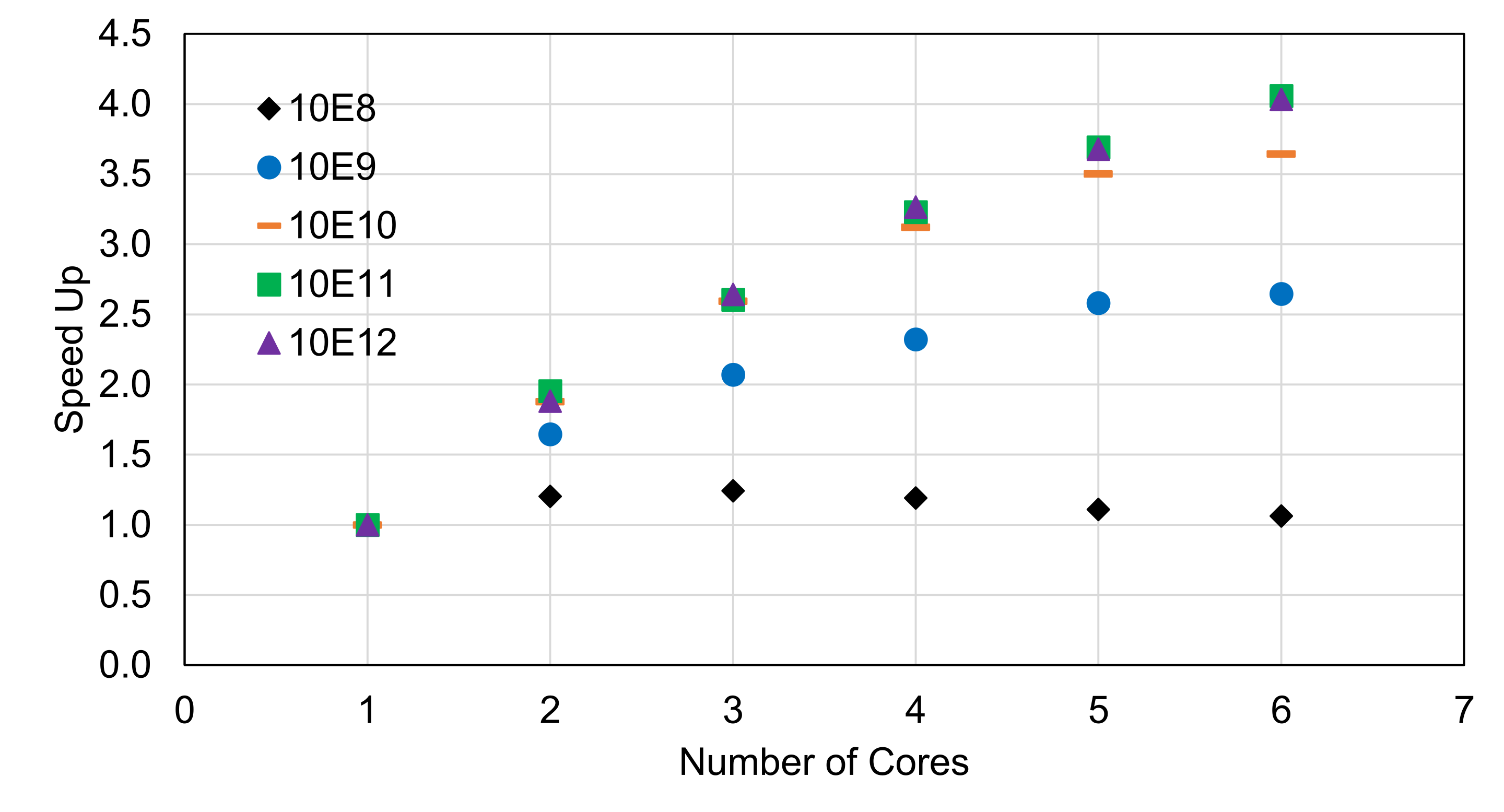

As shown in Figure 4, I ran several different numbers of flips to examine how speed up is influenced by problem size. For 10E8 flips, there is very little speed up across the board which suggests that the problem size is not large enough to overcome the parallel overhead. For flips 10E9, 10E10, and 10E11, the corresponding scaling increases. For 10E12 flips, the scaling is nearly exactly the same as 10E11 flips.

For single core run times, Julia is fastest at 0.404 s followed by Fortran at 3.979 s, C++ at 11.82 s, and Python at 407.2 s. The language with the best parallel scaling is Fortran.

C++, Fortran, Julia, Python Coding Resources

For compiling C++ and Fortran code on Windows/macOS/Linux, I recommend downloading Intel Parallel Studio XE 2018 which is free for students with a .edu email address. For writing C++ and Fortran code on Windows 10 and macOS, I recommend downloading Visual Studio IDE which is also free for students. There is a bit of a learning curve with writing code, compiling, and optimizing your code with Visual Studio, but in general, it’s easier than using g++ or gfortran with a standard text editor. You will need to install the Intel compiler first and then install Visual Studio second with a special option selected (“Desktop development with C++”).. Here are links to a C++ cheat sheet and a Fortran cheat sheet.

The best Python distribution is Anaconda Python and it’s available on Windows, macOS, and Linux. If you’ve never used Python before, I recommend using Python 3.6 and sticking with that for a while (even if 3.7 comes out). I’m still on Python 2.7, but I’ll make the move soon. The best way to code Python is with the Spyder IDE (included in the Anaconda distribution). Those coming from MATLAB will feel more comfortable with Spyder since the UI is similar. Another reason to use Spyder is that it forces you to use best practices (indenting properly, etc.) and tells you when you’re missing something or made a mistake prior to running. Here is a Python cheat sheet.

Julia is still in beta (v0.6.4) so any examples or books you find may not be exactly correct. Google is your friend. The Julia website lists several ways to run Julia, but the way I’m using it is JuliaPro which includes a customized Atom editor called Juno IDE, a debugger, and many packages for plotting, optimization, machine learning, etc. Here is a Julia cheat sheet; it’s for an older version (0.4), but most of it probably is the same.

There are 4818 words in this post.